Art as Therapy: A philosopher’s perspective

Mooching for philosophy podcasts, I came across one by Alain de Botton. In the past, I’ve had little patience for much of what he says since I heard him talk about how money was unimportant and didn’t matter. There was he, all-wise and knowing it all, whilst sitting on an inheritance worth millions. I thought he was a bit of a dickhead. I was ridiculously broke back then, to the point I struggled to pay the rent. Still, philosophy teaches us to focus on the message, not the messenger. When I found his musings on art, I figured it was only fair to see what he had to say.

I began this post in the summer of 2017 and am picking it up now because I desperately need a distraction from personal and global concerns. I often find solace in art and figured I should probably lean heavily on all of my crutches for the foreseeable. It might be worth mentioning he was promoting a book he’s written, which argues that art can be a form of self-help. He also asserts there’s nothing wrong with self-help as a concept, just the books. He’s also plugging his School of Life institution. What follows is a lazy-arsed synopsis type of thing with some commentary thrown in.

His introduction begins with an explanation of how religion is on the decline. Theodore Zeldin, a cultural historian, said art is our new religion, and museums are our cathedrals. The idea is that culture is suited to replace religion. He further explains that church influence declined rapidly after the mid-19th century. Some people were concerned about what would happen when there was no longer a god to hold a society together. Critics such as John Ruskin and Matthew Arnold argued that Cultural stuff like philosophy, art, and literature could replace scripture. De Botton says this idea has primarily failed. The main reason is that we can’t take our spiritual woes to any great art institution. We’d likely get sectioned or arrested if we went to a museum or gallery and asked for help. He begins to question what we can do if we need answers to the more significant questions in life. De Botton ruins the next few minutes by saying that stupid people read self-help. He says there’s nothing wrong with the concept of self-help, just the way it’s been done so far. Interestingly enough, what he’s promoting seems remarkably similar to self-help.

De Botton’s comments here are a little unfair because many intelligent people rely on self-help to look for new ways to deal with old problems. I get tired when I hear people saying that faith in religion or anything spiritual or supernatural is reserved for the mentally challenged. Intelligence has nothing to do with whichever part of the brain is responsible for belief.

I find it interesting that he feels there is a problem with how art is framed. He criticises how art is arranged chronologically. He informs us that all great religious art had the sole purpose of inspiring religious devotion, and it’s all mixed up according to its theological purpose and not organised chronologically. He then argues that we should arrange art according to the needs of our psyche, and I agree with this to a point because it makes more sense. Although, I also feel art can affect each of us differently.

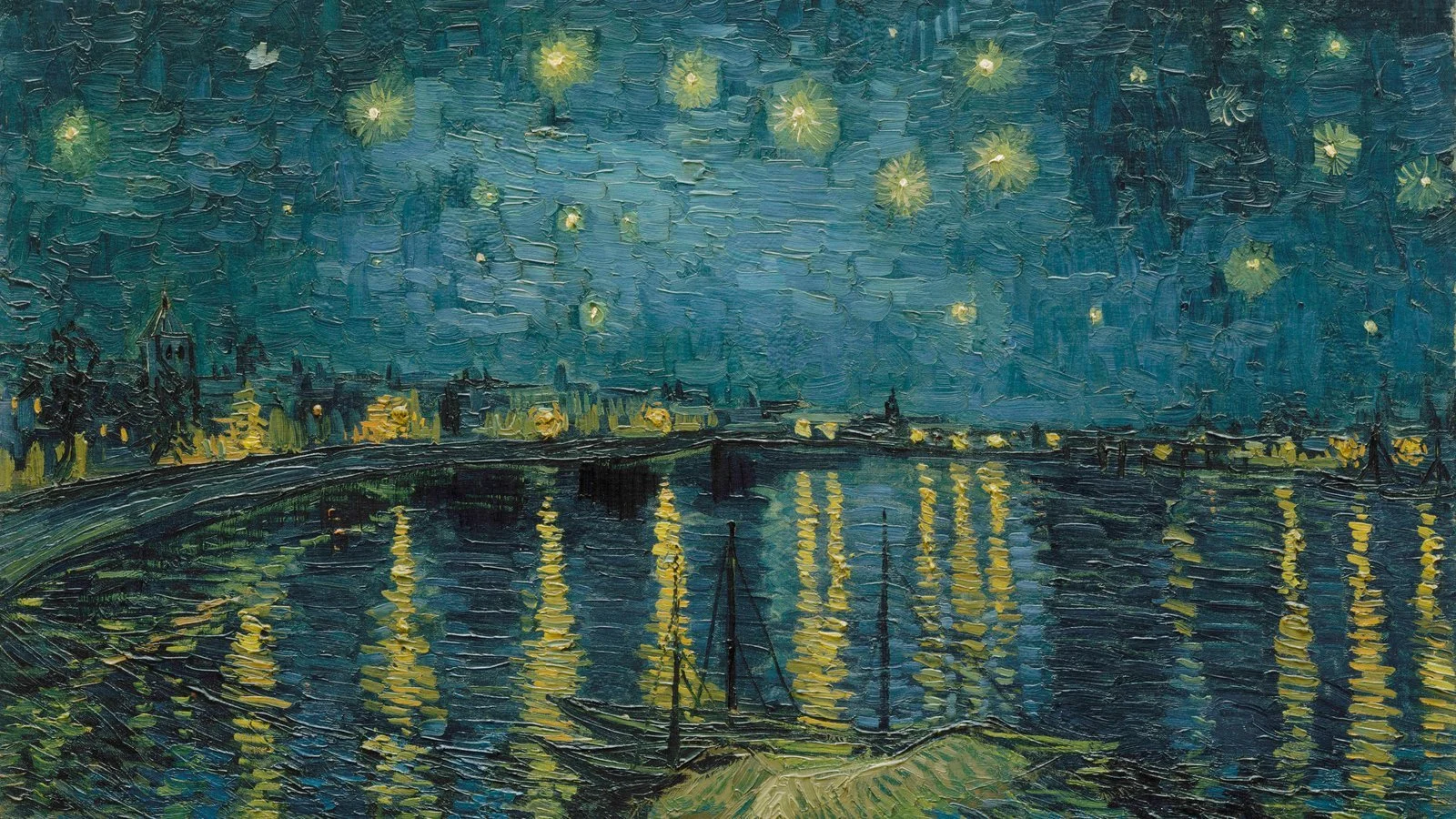

De Botton feels that art can alleviate sorrow and bring hope. This is certainly true for me, but maybe not everyone, and I don’t feel it’s powerful enough for all instances. Literature and philosophy probably have more strength in some cases.

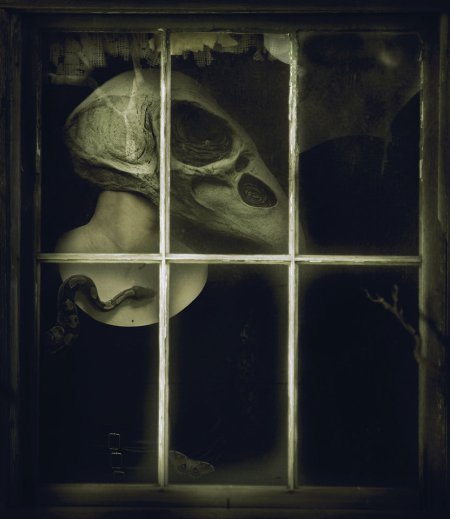

Interestingly, he mentions the art world doesn’t like pretty art because there’s a fear people will be less aware of the darkness in the world. He partially disagrees and says that the more affected you are by something pretty or moving, you are more likely to be aware of the darkness. This is bullshit. Pure and simple. Those aware of the darkness often have an affinity for dark art and that which is humorous but quirky. People who like nothing but pretty are generally noted for their shallowness and reluctance to face anything with a shadow. I am someone who has spent the last five years or so sharing excessive amounts of imagery around various forms of social media. I’ve found that those most drawn to something pretty and happy are the psychically unbalanced ones. They’re the ones who prefer denial and daydreams to reality and balance. Don’t get me wrong; I like to see pictures of pretty things too; I think we desperately need them, especially during times of suffering. The more I’m overburdened, the more I need to see pastel shades and images that reflect something calming or lighter in emotional tone. Most people don’t want to see macabre or grotesque art; that’s why it’s a niche market. Most people don’t actually use art as a form of therapy either; they don’t even question why they think something is pretty or attractive. They certainly don’t stop to think about the emotions it provokes.

According to de Botton, art reminds us we are not alone in our suffering. He discusses how we all fear being a loser and a failure and how the dominant cultural model says we must pretend to be fine. I can see how this is true to an extent. There is a lack of emotional honesty and a reluctance to express the darker stuff. Art does provide a way to connect with the feelings we find unacceptable or challenging to acknowledge.

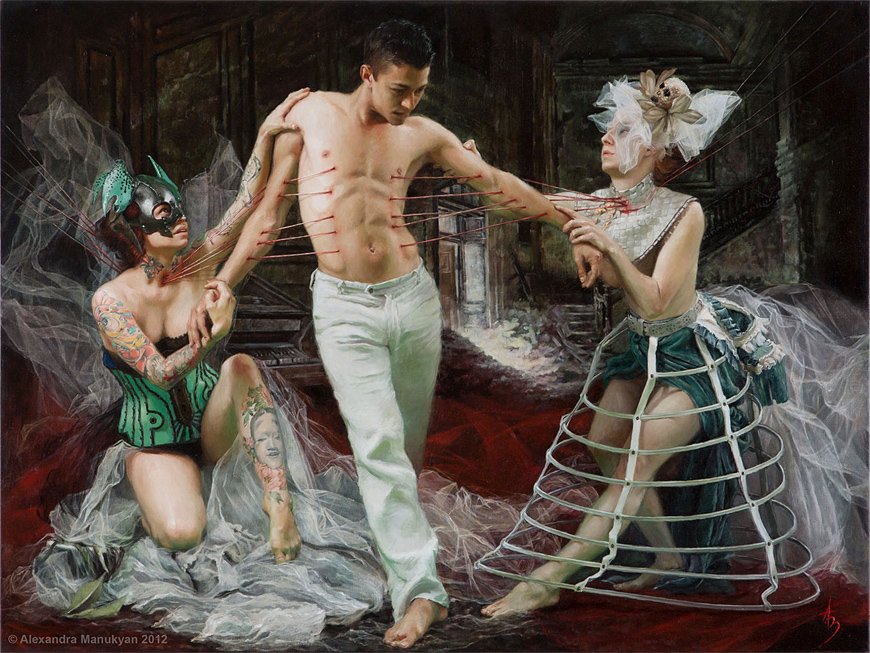

De Botton addresses how he thinks art can rebalance us and says the kind of art that attracts us contains a part of our missing pieces. He suggests looking at what you lack in reality and what the art you’re attracted to offers you. He wants us to ask what we’re compensating for when viewing the art we’re attracted to. Further explaining, he feels we have lost the connection to calm and serenity because of the modern world’s stresses. He explains how this is shown in the popular types of kitchen styles.

Role models have often been used in art to inspire desirable qualities. He explains how staring at Buddha is supposed to inspire you to be more like him. I can understand and agree with this to some extent. Still, I part company with him when he talks about abstract art being useful. I’m not convinced. The more abstract, the less useful on the whole. If I’m having a hard time with a shitty emotion, I want to see art that reflects how I feel, and if that means looking at pictures with ill-formed demons and darkness, then that’s what I need to see. I do appreciate that he mentions how art draws our attention to the every day in a meaningful way and makes the mundane stuff beautiful again.

He circles back to making arguments to arrange art according to the subject. He started to get on my nerves when he referred to a painting with a previously high-status person begging for alms and commented about how it happens to all of us. He said that we all inevitably suffer a loss of face at some point in our lives so we can identify with the picture. He further spoke of how everyone ends up being looked after by others, or we end up in a position of weakness. The problem I have here is one of relativity; not the Einstein version, but the one which says all suffering is relative. That’s Western-thinking bullshit which serves to alleviate guilt. He does mention the fear of death and mortality; the denial of death is a significant interest of mine, so I’m glad it got a mention. He suggests art can help us know how to live and die; I’m not convinced. I think we need words for that. I agree with him when he says we can lose perspective quickly when anxious, and art can calm us down. He points out that images, such as the ones from the Hubble, can make us feel small in a good way. De Botton points out that love should have its own section in a gallery because so many things can go wrong. The first thing he mentions is that we always feel really grateful at the beginning, which is one thing that disappears with time. He sees it as a failure of love that we lose curiosity in the other.

He makes interesting points throughout this lecture, and it’s worth watching if you actively use any of the arts as a form of therapy. My main point of criticism would be that I don’t think de Botton really knows what he’s talking about. I think he likes the idea but is as guilty of paying lip service to it as those he claims to be guilty of doing so. Using art as a form of therapy is not for the faint of heart, and neither can you be shallow nor superficial in your approach. It is not enough to think you’re aware of darkness if you’re affected by happy pictures; that IS a classic self-help mistake that can cause long-term damage. Actual therapy takes you through the darkness to shine light onto the shadows. It makes you sit in your discomfort until you realise the feeling will not cause you physical harm. It’s a complex process. Using art as therapy is akin to entering into a dialogue, but instead of a person, you’re using a picture. But, this is all just me and my thoughts. Watch the video, and see what you think.

Recent Posts

Categories

Tags

- Bird 9

- Clouds 2

- Distance 1

- Birdcage 1

- Art as Therapy 2

- Egg 1

- Kraken 2

- Cards 2

- Crown 1

- Fly 1

- Grief 1

- Endings 4

- Bed 1

- Dreams 1

- Death 2

- Balloon 1

- Cobwebs 1

- Cogs 1

- Gramophone 1

- Invisible Man 1

- Bridge 1

- Bubble 1

- Chessboard 2

- Dice 1

- Boat 3

- Box 1

- Hollow Man 1

- Mask 2

- Bandages 2

- Bones 3

- Origami 1

- Books 1

- Male Ego 1

- Buddha 1

- Face 1

- Cone Head 1

- Hammer 1

- Horns 1

- Mermaid 1

- Mirroring 1

- Ostrich 1

- Halo 1

- Nun 1

- Hair 1

- Hoop skirt 1

- Infidelity 1

- Desert 1

- Blindfold 1

- Caught 1

- Dreamcatcher 1